Economic Empowerment x CRSV

ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT X CONFLICT-RELATED SEXUAL VIOLENCE

| “One such priority, as frequently articulated by survivors I meet in warzones around the world, is economic empowerment. They make the link between their physical insecurity and economic and food insecurity and share with me how economic support fosters self-sufficiency, self-esteem, and resilience, which in turn reduces their exposure to risk, and how dignified access to safe work bolsters their perceived worth and value in the eyes of their community.”

SRSG-SVC Pramila Patten’s Remarks for Private Sector Event, 21 September 2022, New York |

Economic empowerment is a critical factor in addressing the nexus between conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) and the socioeconomic status of women and girls. This page aims to clarify the connection between CRSV and economic empowerment, emphasising how the lack of economic opportunities exposes women and girls to various forms of sexual violence, including sexual exploitation and forced marriages. Highlighting the urgent need for women’s and girls’ economic empowerment illuminates its role in fostering social stability and resilience within conflict settings. Ultimately, promoting women’s economic empowerment is an essential and strategic imperative for achieving broader societal benefits, such as improved public health, education, and governance.

I. What is Economic Empowerment?

a. Definitions

Economic empowerment1 is defined by the OECD as individuals’ capacity to “participate in, contribute to and benefit from growth processes in ways that recognise the value of their contributions, respect their dignity and make it possible to negotiate a fairer distribution of the benefits of growth” (WB).

According to ICRW, economic empowerment consists of two interconnected elements: economic advancement and the exercise of power and agency. These elements are interdependent and essential for improving the lives of individuals and their families. Achieving economic progress enhances individuals’ power and agency; when individuals can control and participate in the allocation of resources (power) and make and define choices (agency), they are better positioned to achieve economic growth.

Economic empowerment is also defined by UN Women as “a transformative, collective process through which economic systems become just, equitable and prosperous, and through which all women enjoy their economic and social rights, exercise agency and power in ways that challenge inequalities and level the playing field and gain equal rights and access to ownership of and control over resources, assets, income, time and their own lives. The key elements of economic empowerment are equal rights and access to ownership and control over resources; agency, power and autonomy; and policies, institutions and norms” (UN Women).

Economic Security, as an essential component of economic empowerment, pertains to “the ability of individuals, households or communities to cover their essential needs sustainably and with dignity” (ICRC).

1 Empowerment can be defined as “the granting of the power, right, or authority to perform various acts or duties”, whereby an individual has the agency and resources to accomplish a given task. (WB)

II. Economic Empowerment in the Context of Conflict

a. The economic cost of conflict

Conflict represents a major impediment for the realisation of economic empowerment. In addition to causing immense human suffering, exposure to intense conflict severely impacts economic development, provokes large outflows of refugees, decreases life expectancy, and shortens educational opportunities (IMF, ICG, UNESCO Institute). As such, the integration of economic empowerment initiatives in humanitarian programming is essential to mitigate and respond to these impacts and prevent further harm to individuals affected by conflict.

Conflict and Economic Development

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) indicates that the destruction of infrastructure, institutions and human capital, the loss of human life, and political instability resulting from armed conflict significantly impede investment and economic growth.

At the national level, conflict has a strong impact on public finances, with reduced tax revenues and higher military spending leading to increased fiscal deficits and public debt. This often results in the diversion of funds away from social and developmental programmes, worsening the impact of the conflict (IMF). For example, a study carried out in 2016 by the International Growth Centre (IGC). shows that civil wars have a large and significant aggregate impact on macroeconomic indicators such as GDP and trade, and that insecurity spread by violence notably creates large increases in labour and transport costs.

At the regional level, conflicts can have strong spillover effects, either by directly spreading conflict to neighbouring countries or by indirectly disrupting economic activities and trade and creating social tensions due to a significant influx of refugees (IMF). Large scale displacement further incurs significant costs for hosting countries. The ICG indicates that in 2016, Pakistan hosted more than 50 million refugees and IDPs, mostly coming from Afghanistan, with an estimated 93 billion USD in associated costs (IDMC, UNHCR). According to the International Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), the number of IDPs by conflict and violence as of 31 December 2023 is 9.1m in Sudan and 6.7m in DRC.

Conflict and Education

Conflict also has a dire effect on education, an essential driver of economic empowerment. It can result in the physical harm, death or displacement of teachers, staff and students. For example, more than two thirds of teachers were killed or displaced as a result of the Rwandan Genocide (UNESCO Institute). Furthermore, the GCPEA reports that in 2020-2021, more than 9,000 students and educators were killed, abducted, arrested or harmed in at least 85 countries.

Attacks on educational facilities resulting from armed conflict also impose strong obstacles to education. According to the GCPEA, more than 5,000 attacks on educational facilities and incidents of military use of school and universities occurred in 2020 and 2021, representing on average six attacks each day.

The impacts of conflict on schooling levels can directly limit the economic empowerment of children in the long term. Based on various studies analysing the intersection between political violence, schooling and income, the ICG reports that reduced education outcomes may translate into eventual impacts on wages.

| “Without access to education, a generation of children living in conflict will grow up without the skills they need to contribute to their countries and economies, exacerbating the already desperate situation for millions of children and their families” (UNICEF). |

Particularly in contexts of weak institutions, fragile states struggle to maintain resilience to conflict and its economic impacts. Thus, building resilience through economic empowerment is essential to enable systems, communities and societies to “resist, absorb, accommodate, adapt to, transform and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner” (UNDRR). Conflict is likely to disproportionately affect people, making it essential to provide immediate support to the most vulnerable and marginalised groups, including minorities, displaced persons, refugees, and the communities that host them.

b. Who is vulnerable to economic insecurity?

Armed conflict exacerbates the preexisting economic vulnerabilities of specific groups, such as women, children, people with disabilities and persons of diverse sexual orientation and gender identity.

Women and Girls

| “It is a product of gender discrimination that 60% of those who go chronically hungry are women and girls; that, globally, women earn less than men; and that nearly two thirds of the world’s illiterate adults are women. It is the product of biased social norms that, in the face of poverty and social upheaval, it is girls who are forced into child marriage, who are viewed by their family as a liability, and who forego food, healthcare and education.”

Statement of SRSG-SVC Pramila Patten at the 2018 Security Council Open Debate on CRSV, 2018 |

In nearly every country, women work longer hours than men, but are usually paid less and are more likely to live in poverty (UNFPA).

In subsistence economies2: women spend much of the day performing unpaid domestic work. Working in such informal or “grey” economies leaves women without any protection of labour laws or social benefits, such as pension, health insurance or paid sick leave (UN Women). The need for women’s unpaid labour often increases with economic shocks, including those resulting from armed conflict.

Care Economy: Women also shoulder a disproportionate share of unpaid care work around the world which constitutes a root cause of women’s economic and social disempowerment (UN Women). Care work can be defined as looking after the physical, psychological, emotional and developmental needs of one or more other people (EIGE). According to the ILO, women across the world spend two to 10 times the amount of time men spend each day on care, meaning that working women everywhere must reconcile the “double burden” or the “second shift”. As care needs continue to expand and diversify, new solutions to care are needed, especially targeting women and girls in conflict settings.

The differences in the work patterns of men and women, and the ‘invisibility’ of work that is not included in the formal economy lead to lower entitlements to women than to men (UNFPA). By the time girls and boys become adults, females generally work longer hours than males, have less experience in the labour force, earn less income and have less leisure, recreation or rest time. This creates important economic vulnerabilities which are exacerbated by conflict, making women much more likely to face economic insecurity, as a result of both increasing demands and expectations for unpaid work and even lower access to resources as they become scarcer during conflict.

| “Together, we have to ensure that girls have the same access to education than boys, that girls are valued as much as their male counterparts, that they have access to nutrition, that gender discrimination – de facto and de jure- is done away with, that equal opportunity in the work place exists and that women have full participation in politics.”

Statement of former SRSG-SVC Zainab Hawa Bangura at the 30th Anniversary of the CEDAW, 2012 |

Specific subgroups of women are particularly affected economically by armed conflict:

Rural women: Rural women frequently face greater difficulties due to inadequate health and social services and unequal access to land and natural resources. In conflict settings, these challenges become more severe, impacting their employment and reintegration. The breakdown of services in such contexts often leads to food insecurity, inadequate shelter, loss of property, and limited access to water. Widows, women with disabilities, older women, single women without family support, and female-headed households are particularly vulnerable, experiencing heightened economic hardship and often lacking employment opportunities and means for economic survival (S/RES/1889).

Displaced women: Displaced women face precarious conditions in conflict and post-conflict settings due to unequal access to education, income generation, and skills training, poor reproductive health care, and exclusion from decision-making processes (S/RES/1889).

2 An economy in which people produce food, clothes, etc. for their own use, and where food, etc. is not bought or sold. (Cambridge Business English Dictionary).

Other Intersecting Vulnerabilities

Persons with disabilities: Persons with disabilities will particularly endure the consequences of war, which involves the destruction of infrastructures they use in order to access all kinds of goods and services (IRRC). According to OCHA, in 2020, households in Syria with more than one member with a disability were 9% less likely to be able to meet their basic needs than other households.

Children: Children are disproportionately affected by armed conflict, both in the immediate and long-term aspects of their lives. As of 2024, approximately 460 million children live in conflict zones facing direct threats to their safety and well-being (UNICEF). These children are not only exposed to violence and instability but also experience disruptions to their education, leading to severe economic insecurity. This instability makes them vulnerable to recruitment by armed groups, forced labour, child marriage, and other grave human rights violations (Save The Children Canada). While girls only made up 15% of UN-reported cases of recruitment in 2020, they are often targeted to act as spies, to lay mines and improvised explosive devices, or to act as suicide bombers because they are less likely to draw attention. Their vulnerability, low status, and gender also make them susceptible to widespread abuse. Additionally, the disruption of schooling and normal childhood activities hinders children’s future job prospects, trapping them in cycles of poverty.

Ethnicity: According to the Secretary-General’s report on CRSV, the profile of a survivor often includes individuals who are actual, or are perceived to be, members of persecuted political, ethnic, or religious minorities (S/2023/413). In 2022, in Afghanistan, extreme poverty exacerbated harmful coping mechanisms, including forced marriage, as women and girls were deprived of educational and economic opportunities owing to discriminatory restrictions on their employment and mobility. In particular, women and girls from ethnic minorities were at particular risk due to facing increasing marginalisation, prejudice and forced evictions (Amnesty International).

III. The Nexus between CRSV and Economic Empowerment

| “Sexual exploitation, including forced prostitution as a basic means of survival (sometimes referred to as “survival sex”), is rampant. This is sexual violence driven by economic desperation where women and girls are compelled to prostitute themselves for less than a dollar in order to survive another day.”

Statement of SRSG-SVC Pramila Patten at the 2023 UN Security Council Open Debate on CRSV |

a. What is conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV)?

Conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) can be defined as “rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, forced abortion, enforced sterilization, forced marriage, and any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity perpetrated against women, men, girls or boys that is directly or indirectly linked to a conflict” (S/2024/292).

b. How does economic insecurity intersect with CRSV?

| “It is evident that food insecurity increases the risk of exposure to sexual violence and conversely that sexual violence often leads to socioeconomic marginalisation, increasing the risks of poverty and food insecurity.” (Secretary-General’s Report on CRSV in 2023) |

Economic insecurity is both a driver and a consequence of CRSV.

Driver

Situations of extreme poverty and inequality leads vulnerable individuals to engage in harmful coping mechanisms in times of conflict, such as exchanging sexual favours for money, shelter, food or other goods under circumstances that exposes them to sexual exploitation and violence, as well as to HIV infection and other STDs. Furthermore, economic insecurity can provide increased opportunities for perpetrators when vulnerable individuals are isolated while conducting livelihood activities. This notably impacts rural women, who are often required to walk long distances to access essential goods and services, such as fuel and firewood, increasing the risks of interacting with armed actors. When faced with food insecurity and lack of basic necessities, conflict-affected groups are also at increased risks of forced and child marriage and human trafficking.

Consequence

CRSV has profound economic implications for survivors. Survivors often face significant social stigma, leading to socio-economic marginalisation and restricting their access to community resources and economic opportunities, impeding their economic reintegration and stability (2023 Annual Report on CRSV). Moreover, the psychological consequences of CRSV, such as depression, anxiety, and reduced self-esteem, can inhibit survivors from pursuing educational and entrepreneurial activities, further limiting their economic empowerment. This affects survivors’ personal recovery but can also exacerbate their vulnerability to further harm. Furthermore, the economic empowerment of survivors is necessary to ensure community resilience, cohesion and recovery. To enable the latter, the stigma and exclusion of survivors must be addressed collectively, while providing them with the opportunities to contribute to their communities’ economies and overall well-being.

Thus, to avoid perpetrating the cycle of economic insecurity and CRSV, it is crucial to implement comprehensive support systems that include psychosocial support, community rebuilding initiatives and economic empowerment programmes.

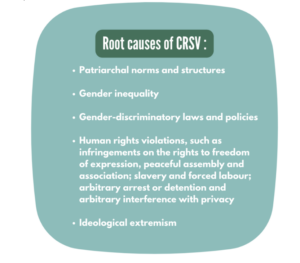

Key 2023 Figures: Economic Factors of Conflict-Related Sexual Violence (2023 Annual Report on CRSV)

Reccomendation 95(c): To mitigate the risks of sexual violence associated with livelihood activities, including those impacted by climate-related security risks, by building community resilience and ensuring that women and survivors of conflict-related sexual violence have safe access to employment and socioeconomic reintegration […]. |

c. Economic empowerment initiatives

Economic empowerment interventions are essential for both the prevention and response to CRSV, allowing to bolster resilience, decrease vulnerability, mitigate the risk of CRSV during emergencies, and ensure the fulfilment of the needs of survivors, families and communities (GBVAoR).

Prevention of CRSV

Research demonstrates that investing in economic empowerment and livelihood programs for women immediately following emergencies effectively reduces their vulnerability to gender-based violence (GBV), including sexual exploitation and abuse (GBVAoR). This can notably be done through vocational training and skills development, and access to employment opportunities, social protection programmes and educational support.

| Engagement with the private sector

According to a white paper developed by UN Action and CTG, the private sector, as the world’s largest employer, can play a critical role in preventing CRSV through the provision of stable and equitable employment opportunities. Secure employment not only mitigates economic hardship but also enhances individuals’ financial independence, thereby reducing their vulnerabilities to CRSV. Furthermore, by fostering inclusive and respectful workplace cultures, businesses contribute to broader societal shifts towards gender equality. This proactive approach challenges and diminishes the discriminatory norms and power imbalances that often underpin CRSV. Therefore, the creation and promotion of employment opportunities are essential strategies for CRSV prevention, as they address economic insecurity and cultivate a culture of respect and inclusion that positively influences societal attitudes and behaviours. |

Response to CRSV

Accelerating economic empowerment constitutes a key component of the comprehensive multi-sectoral support needed by survivors of CRSV. By initiating and investing in economic empowerment initiatives following incidents of CRSV, survivors can achieve financial independence, access employment opportunities, and engage in economic decision-making processes. This not only supports their effective reintegration into society but also enhances the well-being of their families and communities, while establishing a direct path towards gender equality, poverty alleviation, and inclusive economic development (UN Action). More broadly, emphasising the economic empowerment of women and girls is essential to realise women’s rights and gender equality, and to achieve development goals, such as economic growth, poverty reduction, health, education and welfare, ultimately reducing women and girls’ vulnerabilities to CRSV (ICRW).

Economic empowerment as a response to CRSV supports global efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

d. Target groups for economic empowerment X CRSV initiatives

To address the intersection between CRSV and economic insecurity, it is crucial to target both vulnerable groups at heightened risk of economic instability and survivors of CRSV with economic empowerment initiatives. Therefore, target groups include, but are not limited to:

Displaced Women and Girls

UNHCR reports that women and girls are increasingly facing risks of exploitation, trafficking, child marriage and intimate partner violence in refugee camps. This is due to prevailing insecurity resulting from criminal activities and the presence of armed groups in refugee and IDP camps, as well as the lack of education and employment opportunities. These factors exacerbate the risks of CRSV, as seen in refugee and IDP camps in South Sudan, Mali, Bangladesh, Sudan and the DRC, among others.

| Case study: Kutupalong refugee camp in Cox Bazaar, Bangladesh

“Education is a basic human right. But today, why [do] we have not this right? Are we not human?” Sawyeddollah, a Rohingya refugee in the Cox’s Bazar camps, November 2019 (Human Rights Watch) Kutupalong, known as the world’s largest refugee settlement, mainly inhabited by Rohingya refugees fleeing the armed conflict in Myanmar, is marred by insecurity and criminal activities, notably influenced by the presence of eleven armed groups, including the ARSA, RSO, Munna Gang, and Isami Mahaz (OCCRP). In the camp, women and girls find their lives constrained by the authoritative control exerted by civil communities and armed groups, especially concerning matters of marriage, education and employment, limiting their capacity to deviate from traditional gender norms and impeding their economic independence and security. For example, Human Rights Watch reported that the ARSA issued fatwas restricting women and girls’ access to work and education, notably forcing 150 to resign from teaching positions in learning centres. Such economic insecurity has led to increased child marriages, prostitution and human trafficking, resulting in significant CRSV. |

Women and their Children Born of CRSV

Survivors and children born out of rape grapple with a range of severe and specific challenges, stemming from long-term physical injuries and psychological trauma inflicted during captivity and compounded with indefinite stay in IDP sites owing to discriminatory birth registration laws that prevent children from obtaining citizenship, insecurity, and alleged association with non-state armed groups (2023 Annual Report on CRSV). Called derogatory labels such as “children of hate”, “children of shame” and “children of the enemy”, children born of rape are at heightened risk of infanticide, abandonment, and statelessness, and they frequently encounter significant barriers to accessing education and healthcare (S/RES/2467 | Centre for WPS Research at LSE). The burden of “forced motherhood” adds another layer of economic and social strain, as these women often face compounded difficulties including poverty, homelessness, and limited access to legal reparations. Their stigmatisation, exclusion and ensuing socio-economic insecurity represent a major impediment to their economic empowerment, highlighting the criticality of designing comprehensive initiatives that address stigma, enhance resilience, and improve the overall life chances of both the mothers and their children, fostering their reintegration in post-conflict societies.

Men and Boys

Men and boys who have experienced CRSV often face heightened stigmatisation and ostracisation due to prevailing social norms that depict men as primary protectors and providers. This societal view of men as inherently resilient and economically capable frequently results in inadequate support services tailored to their specific needs and a reluctance to seek help. Consequently, these survivors experience dual exclusion from both their communities and the humanitarian sector, impeding their economic and social reintegration. The unique impacts of CRSV on men and boys—such as shame, stigma, depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation—are often overlooked (Morrison, 2017). To address these challenges effectively, economic empowerment initiatives must also specifically target men and boys, ensuring that they receive the appropriate support and resources necessary for their recovery and reintegration.

Individuals Associated with Terrorist and Extremist Armed Groups

Former combatants and individuals associated with terrorist and extremist armed groups face increased rejection from their communities and mental health challenges (AllianceCPHA). The experience of direct exposure or involvement in the perpetration of violence can cause persistent negative feelings that can hinder socio-economic reintegration (IOM | UNSOM). When compounded with experiences of sexual violence, these effects are further exacerbated. Moreover, former combatants can be the object of mistrust, blame and rejection from community members (UNDP). The reintegration process can be emotionally and socially challenging for both families and entire communities. In the worst cases, the combination of these elements, if not properly addressed, can lead to depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse and suicidal behaviours (IOM | UNSOM). Both the exclusion and mental health burden severely impedes the economic empowerment and reintegration of this group, necessitating specific interventions to meet their needs.

| Case study: Somalia and women associated with Al-Shabaab

In Somalia, women associated with Al-Shaabab (AS) are often survivors of CRSV and face significant stigmatisation, exposing them to grave economic insecurity. Regardless of their roles in and experience with AS, most of the women who left AS live in extreme poverty, with 13% earning less than 40 dollars per month. Moreover, 59% of them are the head of their household and 68% of the households have more than six individuals. Furthermore, they do not have access to resources available to other women and men. For example, based on household surveys, it is estimated that 67% of them do not have access to medical care; 94% have difficulty reading and writing as they barely received formal education. (IOM | UNSOM) Their lack of access to resources is worsened by the distorted teaching on women’s rights they received from AS, as well as the stigmatisation from community members due to their previous association with AS. As a result, these women face a triple burden of displacement, socio-economic exclusion and mental health challenges. See UN Action economic empowerment project in Somalia in the “UN Action Projects” section below |

IV. Economic Empowerment and UN Action

a. UN Action’s engagement in Economic Empowerment

CRSV and the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war has been widely reported to affect women and girls disproportionately. In the 2021 Report of the UN Secretary General on CRSV, it was noted that in almost all the situations of concern covered in the report “sexual violence impeded women’s participation in social, political and economic life, highlighting the importance of addressing the root causes of sexual violence as part of promoting substantive equality in all spheres” (S/2022/272). The majority of survivors in the report’s document cases come from socioeconomically marginalised communities, thus illustrating the vulnerability caused by low economic status that is only worsened as a consequence of CRSV. Moreover, stigma and discriminations surrounding survivors of sexual violence may restrict their access to economic life which is exacerbated for displaced, migrant and refugee women and girls who face heightened socioeconomic exclusion as a result of CRSV, impeding their healing and socioeconomic reintegration (S/2022/77). This economic isolation of survivors worsens their vulnerability to abuse, including to conflict-driven trafficking. Therefore, a holistic survivor-centred approach requires that survivors are heard and that there is investment in the support of survivors, including in the mitigation of the economic effects of sexual violence.

Economic empowerment can be a means of supporting women and girls to participate in existing markets, access work opportunities, voice agency in economic decision-making, and exercise control over their own resources. It can include a vast range of activities that share the purpose of bolstering agency and economic independence and reintegration within groups or communities where they become active contributors and agents of change. Efforts to mitigate the socioeconomic isolation of survivors and increase their access to social services are key to overcome barriers associated with the successful reintegration; however, there remains a paucity in understanding on how best to tailor such services and programmes to meet the needs of survivors of CRSV. In order to integrate economic empowerment as an essential component of the multisectoral support provided to survivors and embody the One UN approach to prevent and respond to CRSV, there must be further coordination and collaboration across sectors and UN entities on key concepts, approaches, best practices, and lessons learned. Therefore, UN Action, as the coordinating mechanism for the UN’ response to CRSV, aims to employ a One UN approach in the prevention and response to CRSV. The network does this by addressing the root causes of sexual violence which disproportionately affect women and girls, including marginalisation and poverty as some of the main drivers of CRSV.

Recently, in line with the priorities of SRSG-SVC Patten, the Chair of the UN Action Network and UN Action’s 2020 – 2025 Strategic Framework, efforts to increase focus on economic empowerment within the network have been accelerated. This has been bolstered by the ITC3 joining UN Action in December 2021, and with its expertise, has taken the lead in framing UN Action’s initiatives in this area. As the thought leader, ITC’s goal – with the support of the UN Action Secretariat – is to host a series of brownbags that provide opportunities for learning and exchange, but also serve as a soft assessment to identify Network priorities for the nexus between economic empowerment and CRSV.

In May 2022 UN Action hosted a preliminary brownbag (co-led by the UN Action Secretariat and ITC), to discuss core Economic Empowerment concepts for survivors of CRSV and establish a foundation to share promising practices and discuss the various approaches used across entities. During the event, ITC provided an introduction to key concepts which was supplemented by presentations on two UN Action-funded projects in Myanmar, implemented by UN Women and UNODC, and Somalia, implemented by UNSOM and IOM. The preliminary brownbag established a baseline and opened a space for information exchange between entities that the Core Group aims to engage with more actively in upcoming brownbags. In November 2022, a second brownbag was hosted with the participation of ITC and UN Action Focal Points to trigger conversations amongst Network members on the concept of economic empowerment to establish a baseline definition and discuss the various approaches used across entities.

b. UN Action projects

This section provides examples of economic empowerment programmes jointly implemented by UN Action entities to address the nexus between economic insecurity and CRSV in situations of concern.

| UN ACTION |

Bosnia Herzegovina (UN WOMEN, IOM, UNDP, UNFPA)

In 2014, UN Women launched a project to seek care, support and justice, to advance the rights and respond to the needs of survivors of CRSV from the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the early 90s, and to provide redress to both them and their families. This joint project combined the expertise and in-country experience of four UN agencies: IOM, UNDP, UNFPA and UN Women, and consisted of three main components: (i) data collection, research and mapping of needs and capacities, (ii) enhancement and expansion of CRSV-sensitive service provision, and (iii) stigma reduction through advocacy and sensitisation. UN Women’s focus included the economic empowerment of survivors of CRSV and their families, the capacity-building of civil society organisations to represent and provide services to CRSV survivors, and the reduction of stigma. Specifically, UN Women implemented targeted economic schemes, engaged in advocacy with employment bureaus, and strengthened referral mechanisms to include institutions responsible for economic rights (UN Women).

Democratic Republic of the Congo (OHCHR and MONUSCO)

In 2022, UN Action funded a project in the DRC aimed at addressing the needs of survivors of CRSV, including by supporting their economic empowerment. This innovative project implemented by OHCHR and MONUSCO reached 755 survivors of CRSV involved in the artisanal mining sector to access medical, psychosocial, legal, and socio-economic reintegration support. The project worked with local women’s cooperatives in 13 conflict-free mining sites and supported the establishment of a One Stop Centre that has already provided assistance to 498 women, 61 girls, 10 boys, and 186 men. The project further included awareness-raising missions and the creation of mobile legal clinics. Legal aid and holistic assistance were provided to those who wished to file complaints. Lastly, two beneficiaries participated in the training of lapidary trainers in Tanzania. Following the training, the two beneficiaries became assistant trainers at the Panzi workshop in September 2022, where nine women were trained in lapidary and jewellery.

Photos: UN Action Project: DRC, {2022-2023}/ Photo credit: Panzi Foundation

Mali (UNFPA and MINUSMA)

In 2023, UN Action funded a project in Mali implemented by UNFPA and MINUSMA that supported over 6,500 beneficiaries through awareness-raising activities and the provision of multi-sectoral and socio-economic reintegration assistance to survivors, children born of rape, and their communities. The project established 24 early-warning mechanism “comités” that identify incidents of CRSV and referred survivors to trained service providers. These services have reached 8,729 people so far, with 364 survivors supported through the One Stop Centre and mobile clinics, and 2,967 survivors having received mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) in IDP camps. Furthermore, more than 2,500 dignity kits were distributed in IDP camps. Despite the closure of MINSUMA, UN Action continued to provide life-saving and critical support to survivors of CRSV in IDP camps, including through the establishment of cash programmes to tackle food insecurity. Through this programme, 450 survivors were empowered using cash and vouchers modalities to respond to GBV/CRSV.

Photos: UN Action Project: Mali. {2023-2024}

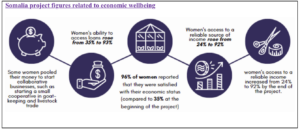

Somalia (IOM, UNSOM)

From April 2020 to March 2021, UN Action piloted the economic empowerment programme “Leveraging the strength of women in Somalia to mitigate CRSV and prevent violent extremism” in Somalia. This project supported the rehabilitation and reintegration of approximately 230 women in Somalia, from Baidoa (Southwest State) and Kismayo (Juabaland state), formerly associated with Al-Shabaab, many of whom are survivors of CRSV. The project used culturally grounded approaches to assist women to recover from trauma, and provided economic empowerment support, ultimately ensuring that these women became active contributors to sustainable peacebuilding in their societies. In partnership with Disengagement, Disassociation, Reintegration and Reconciliation (DDRR) rehabilitation centres and women-led organisations, IOM provided holistic and gender-sensitive services to vulnerable women, including basic education, business development and livelihood skills training to enable them to rebuild their lives. For example, some of the women pooled their money to start a collaborative business that built a small cooperative in goat-keeping and livestock trade (UN Action). Finally, by using survivor-centred psychosocial approaches, IOM and UNSOM created opportunities for women to explore their identities, establish a sense of belonging within their communities, and build trust with other women.

Photos: UN Action Project: Somalia, {2020-2021}

Read more about this project and find stories from survivors here.

South Sudan (ITC, UNFPA, UNMISS)

UN Action funds an economic empowerment programme in Yambio, Juba, Bor and Bentiu in South Sudan since December 2023. Implemented by ITC, UNFPA and UNMISS, this project aims to build the socio-economic resilience of survivors of CRSV. Using a survivor-centred approach, it seeks to improve access to essential medical, psychosocial and legal services through multi-sectoral collaboration and holistic support and help build survivor’s resilience and reintegration through economic empowerment, financial inclusion, advocacy and policy reforms, and community engagement and awareness. The first reporting period, from February to May 2024, focused on strengthening the agency of women, girl, men and boy survivors of CRSV and at-risk groups through medical, psychosocial, legal and economic empowerment. UNFPA supported One Stop Centres to provide CRSV survivors with essential medical, psycho-social, legal and economic assistance. The Center has played a pivotal role in survivors’ economic empowerment, whereby some beneficiaries have already initiated small-scale businesses, like selling oil, sugar, and salt. Furthermore, ITC has conducteda mapping mission and a market assessment in Bor and Yambio to identify conflict-sensitive economic empowerment approaches and quick-win areas where the target groups can be supported to generate income. Despite challenging operational conditions, implementors have made significant progress in increasing income and employment opportunities for CRSV survivors and at-risk groups. As of the time of this writing (Aiugust 2024), this project is still ongoing.

Photo credit: ITC

c. UN Action Member Entities’ Projects

This section provides additional examples of UN Action member entities’ economic empowerment and GBV initiatives, including programmes that support survivors of CRSV in situations of concern.

| UNDP |

Sudan

Since January 2023, UNDP has piloted the project “Achieving Gender Transformational Results in Crisis Context through Women’s Economic Empowerment and GBV Programming” in Sudan, which works towards achieving gender-transformational impact in crisis contexts. The project has been adapted to Sudan’s ongoing violent conflict by placing a strong emphasis on the provision of socio-economic activities which aim to support and empower vulnerable women, including GBV survivors. The project has provided women with significant livelihood opportunities, enabling them to access, use, and control resources, as well as vocational trainings and platforms for information sharing.

Key achievements:

- Livelihoods and food and nutrition security has improved for 750 female headed households who received certified seeds and small ruminants, creating additional income opportunities and enhancing women’s decision making in the household.

- 300 women across six cooperative committees which focus on overcoming gender-specific barriers to credit and lending, have pooled their resources to provide members the necessary resources to establish and run business ventures. 14 women have notably accessed loans from cooperative committees to start food processing businesses.

- 240 women were trained on financial literacy, acquiring the necessary knowledge to manage their finances effectively and ultimately furthering their economic independence.

- 57% of the women participated in vocational skills training in mobile phone repair and maintenance and production of energy efficient stoves. Women have been equipped with practical skills and startup kits to diversify their incomes and enhance their economic resilience.

- Support networks and collaborations among women in six communities have been strengthened through coffee chats, providing platforms for information sharing and collective action to both address GBV and foster community cohesion.

Lebanon

Building on the increased global recognition of the connection between gender-based violence (GBV) and the achievement of inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment, and decent work for all women and men (SDG 8), UNDP implemented from 2018 to 2021, Stronger Together ( معا ً أقوى) ; a gender transformative project in South Lebanon, to pilot interventions that integrate GBV prevention strategies into women’s economic participation (WEP) programming. This project was conducted in partnership with a consortium of international and local organisations consisting of ACTED (consortium leaders), ABAAD, ESDU and DOT. It contributed to building the confidence of women and raising both women and men’s awareness on gender equality issues, which has in turn resulted in changes in their attitudes and practices in relation to gender roles within both private and public spheres. Furthermore, findings showed that the percentage rise in participants benefiting from skills building and leadership development expressing confidence to participate in the labour market increased for Stronger Together participants. 21.7% of women survey respondents said that participating in the Stronger Together programme improved their economic situation.

Afghanistan

UNDP has been working in Afghanistan for more than 50 years on poverty and inequality, governance, resilience, environment, energy and gender equality. As part of its various economic empowerment initiatives targeting vulnerable groups, UNDP has notably focused on the following three areas:

- Access to economic resources for GBV survivors: UNDP’s efforts to create an enabling environment for women’s access to economic resources empowered 160 women-led NGOs/CSOs through capacity building related to management skills and sexual exploitation and abuse risk prevention and response. UNDP carried out a nation-wide survey and stakeholder mapping of GBV and harmful practices to uncover the root causes of GBV, identify key community stakeholders to improve societal behaviours, and provide evidence-based recommendations to inform targeted support. Moreover, UNDP has supported the provision of referral services to 400 GBV and sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment survivors. The totality of GBV cases referred were provided with cash grants to improve financial independence while their cases were addressed. UNDP further established and economically empowered 31 self-help groups through women’s saving associations across the country and created 120 local gender advocates.

- Access to financing: Through its project in Afghanistan, UNDP introduced innovative financing instruments and capacitated local banking institutions to boost the private sector. Together with UNCDF, UNDP notably developed a women’s revolving facility building the capacities of 20 women entrepreneurs. Furthermore, as part of private sector recovery and enhancement of access to finance, 168 businesses, including 67 women-owned businesses, were technically appraised and enabled to graduate from grants to microfinance loans, with a total value of AFN 30,085,000 disbursed.

- Climate-resilient livelihoods support: As part of its programme aiming to promote climate-smart agro-based livelihood to farmers, 261 women farmers were provided with agro-kits comprising of 20 animal husbandry kits, 216 green-house packages, 25 poultry kits, and trainings to support home-based livelihood means and increased income generation. Through containerised farming training and inputs, 100 women-headed households in Jalalabad were supported with farming skills to improve food security.

Myanmar

UNDP implemented a project in Myanmar, where it identified vulnerable communities and facilitated a sequenced engagement involving needs assessments, trust-building, and socio-economic projects, including GBV services, cash for work, startup livelihood assistance for women, and community infrastructure rehabilitation. In peri-urban Yangon, 85% of the 330 (270 youth, 60 women) trainees who completed UNDP’s Technical Vocational Education Training programme secured employment, made possible through a cooperation model established with private companies. Furthermore, in central Rakhine, UNDP, in partnership with local CSOs, trained 411 individuals (31% youth) in various skills, providing grants to 18% of the trainees for business initiation, 75 of which launched small-scale businesses.

| ITC |

Nigeria

The project “SheTrades: Empowering Women in the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA)—Phase II” piloted by ITC in Nigeria aims to empower women entrepreneurs to benefit from trade opportunities created by the AfCFTA. The project helps design a more inclusive AfCFTA by: i) providing women’s business associations with capacity-building, networking platforms and support for effective policy advocacy on AfCFTA Phase II issues; ii) leveraging the private sector to foster women’s economic empowerment through the AfCFTA; iii) working with ECOWAS to strengthen the ecosystem for women; and iv) promoting public private sector dialogues on women and trade across selected countries.

ITC has also implemented the programme “Empowering women and boosting livelihoods through agricultural trade: Leveraging the AfCFTA Phase II” in Nigeria, focused on empowering women producers, processors, and informal and formal traders in agriculture and agro-processing value chains as well as agriculture women-led micro, small and medium enterprises to benefit from trade opportunities created by the AfCFTA through capacity-building, policy research and policy dialogues. Read more about this project here.

Colombia

ITC also leads the “SheTrades Latin America” programme which has the objective to empower and train 1,000 women-led companies in Latin America to enable them to sell their products and services online. The programme was implemented in Colombia from June 2022 to December 2023, during which ITC worked with strategic partner institutions specialised in e-commerce to develop tools and events in Spanish.

| UNFPA |

MENA Region

UNFPA established a programme in the MENA region called “Transcending Social Norms” which focused on making interventions in adult spaces more gender transformative and supporting the economic empowerment of women and girls by getting them to consider other skilling or non-traditional activities that are usually perceived as masculine. Activities were implemented through Women and Girls Safe Spaces which offer women and girls unique opportunities to rebuild the social networks they had lost due to humanitarian conflicts or personal trauma, cultivate valuable life skills that create economic opportunities, and receive professional therapy and support when needed. Although the primary purpose of all Safe Spaces is to enhance the psychosocial wellbeing of those being served, across the eight locations where interventions took place, vocational training activities improved women’s economic outcomes by supporting them to make extra income from home. Read more about this programme here.

| ILO |

Ukraine

In 2022, ILO developed an awareness raising campaign on the risks of human trafficking and labour exploitation targeting refugees, most of whom are women, with the State Labour Inspectorate of Ukraine. ILO leveraged railway trade unions and Ukrainian railways to develop key warning messages and videos which were screened in all inter-city trains within Ukraine and shown 6-7 times per journey. The Railways Trade Unions printed posters with the same messages. As of January 2024, the campaign had reached out to 5.3 million displaced Ukrainians. ILO also rapidly trained 300 Ukrainian labour inspectors on psychological first aid and all Moldovan labour inspectors received a refreshment training on human trafficking and forced labour, with a focus on persons fleeing the war in Ukraine. With ILO support, the State Labour Inspection provided 164,000 businesses, including relocated ones with information on conducting business during martial law, and on employment relationships.

Furthermore, ILO provides support to facilitate the protection and socioeconomic inclusion of refugees in neighbouring countries, particularly in Moldova, in coordination with the Government, UN partners, and local civil society. Interventions include:

- Delivery of humanitarian aid, such as shelter and food, for displaced people in Ukraine and Moldova.

- Inclusion of internally displaced people and refugees in labour markets and education, including by facilitating the recognition of educational credentials and leveraging e-learning solutions developed during the pandemic.

- Prevention of labour exploitation and human trafficking of displaced populations.

- Income support through the facilitation of social payments and cash for work programmes.

- Economic stabilisation measures in relatively safe regions of Ukraine through private sector development, local employment partnerships, entrepreneurship training, and relocation of businesses.

- Financial support to trade unions and employers’ organisations for upgrading services to members (business relocation and business matchmaking with aid industry job referral and legal advisory services).

Additionally, ILO is currently trialling innovative childcare solutions in Ukraine (BohusLOVE) and Moldova (Orange Kids) focusing on accessibility and affordability for all, particularly targeting families with children under three years old. These new models include family-type arrangements, mini kindergartens, and workplace-based solutions. The initiative aims to mitigate the effects of the ongoing conflict with Russia, which has exacerbated the need to engage more women in the labour market. This need is further compounded by a pre-existing lack of affordable and accessible childcare services, which has traditionally hindered women’s participation in the workforce.

Asia-Pacific Region

From 2013 to 2015, in partnership with the Japan Fund for Building Social Safety Nets in Asia and the Pacific, ILO implemented the “Empowering Marginalised and Vulnerable Populations through Community-Based Enterprise Development (C-BED)” project in the Asia-Pacific region. The project aimed to assist ILO constituents and local partners in providing effective, low-cost training and support on entrepreneurship and business development in vulnerable and at-risk communities, such as people living with HIV, sex workers, LGBTQI+ individuals, and men and women with disabilities. The overall project objectives were to: i) improve employment opportunities for poor, vulnerable and marginalised groups through access to skills training on enterprise development; ii) empower vulnerable groups to start or improve their businesses through the new skills acquired; and iii) create an enabling environment for entrepreneurship through establishment and strengthening of networks of implementing social safety net services, providers of working capital, and participants from vulnerable groups.

| IOM |

Jordan

IOM’s “Economic Empowerment and Resilience Programme for Refugees” was designed to decrease the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on refugees and their businesses, while also complementing the short-term and sporadic assistance they received, enabling them to generate income in the longer term. Implemented in Jordan, IOM provided a grant worth USD 2,000 on average for beneficiaries to restart or grow their business based on the viability of their business plan and their capacity to implement it. Tailored to their needs, beneficiaries received skills training to build their understanding of business management and marketing. They also received consumption support monthly cash assistance to cover their basic needs while working on their business development, resulting in the overall empowerment of 32 Syrian refugees in North Jordan and East Amman.

Nigeria

In June 2023, IOM launched the “Enhanced Reintegration for Survivors of Trafficking (ERS)” project, an initiative aimed at empowering survivors of trafficking in Ghana and Nigeria through enhanced reintegration support. Recognising the critical need to address the long-term challenges and risks faced by survivors of trafficking, the ERS project has been developed to offer survivors of human trafficking the necessary tools and resources to foster economic security, while also providing comprehensive support across various dimensions of their reintegration journey. This is being done through the provision of reintegration grants to support the establishment of microbusinesses and the establishment survivor-led support groups and mentoring programs, creating a safe and empowering environment for survivors to share experiences, seek guidance, and build support networks. Reintegration support mentors, including partners from the Government of Ghana, the University of Ghana, NGOs, and the private sector, along with a case management team comprising state and non-state actors in Nigeria, work closely with survivors to provide personalised assistance in business planning, skills development, and accessing relevant resources.

V. Relevant UN Frameworks and Resolutions on Economic Empowerment (and CRSV)

Resolution 2122 (2013): Positions gender equality and women’s empowerment as critical to international peace and security, recognising the differential impact of all violations in conflict on women and girls and calls for consistent application of the Women, Peace and Security agenda across the UN Security Council’s work.

Resolution 1889 (2009): Recognises that there are strong links between women’s social and economic empowerment and the success of post-conflict peacebuilding efforts. This resolution further notes that despite progress, obstacles to strengthening women’s participation in conflict prevention, conflict resolution and peacebuilding remain and women’s capacity to engage in public decision making and economic recovery often does not receive adequate recognition or financing in post-conflict situations. It underlines that funding for women’s early recovery needs is vital to increase women’s empowerment, which can contribute to effective post-conflict peacebuilding.

Resolution 2467 (2019): Encourages concerned Member States and relevant UN entities to support capacity building for women-led and survivor-led organisations and build the capacity of civil society groups to enhance informal community-level protection mechanisms against sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict situations. This resolution further calls to increase support of women’s active and meaningful engagement in peace processes, aiming to strengthen gender equality, women’s empowerment and protection as a means of conflict prevention. It encourages leaders at the national and local level, including community, religious and traditional leaders, as appropriate to avoid the marginalisation and stigmatisation of survivors and their families, as well as, to assist with their social and economic reintegration and that of their children, and to address impunity for these crimes.

Women’s participation in peacebuilding – Report of the Secretary-General (2010): Calls to ensure that adequate financing — both targeted and mainstreamed — is provided to address women’s specific needs, advance gender equality and promote women’s empowerment notably by ensuring that economic recovery prioritises women’s involvement in employment-creation schemes, community-development programmes and the delivery of front-line services. The report further calls for post-conflict employment programmes to specifically target women as a beneficiary group, asking that neither sex receives more than 60% of employment person-days, and to ensure that gender-responsive economic recovery involves the promotion of women as “front-line” service-delivery agents — for example, in the areas of health care, agricultural extension and natural-resource management. It indicates that in primarily agrarian post-conflict societies, policy must target the needs and capacities of rural women — for instance, through the procurement of food from women smallholders and that barriers to credit, including insecure land title, require focused attention.

Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) General recommendation No. 30 on women in conflict prevention, conflict and post-conflict situations (2013): Recognises that women and girls are at the front line of suffering during armed conflict, bearing the brunt of the socioeconomic dimensions. The Committee recommends that States parties develop and disseminate standard operating procedures and referral pathways to link security actors with service providers on gender-based violence, including one-stop shops offering medical, legal and psychosocial services for sexual violence survivors, multipurpose community centres that link immediate assistance to economic and social empowerment and reintegration, and mobile clinics. It further calls to: i) ensure that economic recovery strategies promote gender equality as a necessary pre-condition for a sustainable post-conflict economy, and target women working in both the formal and the informal employment sectors; ii) design specific interventions to leverage opportunities for women’s economic empowerment, in particular for rural women and other disadvantaged groups of women; iii) ensure that women are involved in the design of those strategies and programmes and in their monitoring; and iv) effectively address all barriers to women’s equitable participation in those programmes.

VI. UN Entities’ Strategies and Policies on Economic Empowerment x CRSV

| UNDP |

UNDP’s 10-Point Action Agenda (10 PAA) for Advancing Gender Equality in Crisis Settings

The 10-Point Action Agenda (10 PAA) provides a comprehensive roadmap to connect the prevention of CRSV with economic empowerment and other critical points. This agenda employs a whole system thinking approach, which emphasises the interconnections and interdependencies within the entire system. By integrating various elements such as social, economic, and political factors, the 10 PAA ensures a holistic and transformative approach to addressing CRSV. It highlights the need for integration across different sectors and promotes systemic change by addressing root causes and promoting sustainable solutions.

UNDP’s Gender Equality Strategy 2022-2025

This Strategy advocates for integrating, preventing, and responding to gender-based violence across various portfolios such as economic recovery, livelihoods, climate change, elections, and addressing the rising rates of violence against women politicians. It recognises both the risks and opportunities presented by digitalisation, the initiative leverages digital technologies to improve services and address cyber-violence, especially against young women.

| UN Women |

Women’s Economic Empowerment Strategy

The Women’s Economic Empowerment Strategy articulates UN Women’s vision for enabling women’s economic agency, autonomy and well-being. Anchored in UN Women’s Strategic Plan 2022–2025 and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, its objective is to provide a framework that galvanises internal and external stakeholders to work together at the local, national and global level through transformative solutions that improve the lives of women and girls with no one left behind. The strategy has been informed by data-driven analysis, extensive consultations and UN Women’s Independent Evaluation Service’s 2022 corporate evaluation of UN Women’s contribution to women’s economic empowerment (WEE).

| DPPA, OHCHR, OSRSG-SVC |

This Handbook is intended to serve as a practical guide to support the implementation of the CRSV mandate by United Nations Field Missions, including Peacekeeping Operations and Special Political Missions. It serves both as guidance for civilian, military, and police personnel deployed to United Nations Field Missions and as a pre-deployment orientation tool for future Mission personnel. The Handbook defines key concepts and delineates the responsibilities of civilian, military, and police components within United Nations Field Missions to help prevent and respond to CRSV. Using case studies from various Field Missions, it focuses on common challenges and proposes recommendations. The guidance and best practice described in the Handbook can be built upon and adjusted to suit the specific context and needs of United Nations Field Missions.

VI. Learning Resources on Economic Empowerment x CRSV

a. Publications, Blogs, and E-Courses applicable to Economic Empowerment X CRSV

| UNDP |

This Toolkit on Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in Crisis and Recovery Settings provides guidance on how to enable the leadership of women and girls while making sure that their specific needs are met. It consists of seven thematic Guidance Notes covering UNDP’s main areas of work in crisis and recovery contexts. Each Note offers concrete entry points and proven approaches for gender-equitable, transformative recovery and resilience programming. Additional Tip Sheets complement the Notes with fast facts and overviews of policy frameworks, concepts, indicators and innovative practices.

This report contains an overview and concrete recommendations to take up the main findings of four UNDP pilots funded by the Republic of Korea to gather evidence about what works to integrate a “GBV lens” into broader development interventions with the aim to prevent and respond to GBV. The recommendations are practical and will help development professionals – particularly UNDP staff with policy or programmatic responsibilities – to assess whether a particular intervention has the conditions to integrate a “GBV lens” as part of its core development objectives. All UNDP programmes and policies encounter at some point GBV and thus should be made aware of the possibility of addressing and preventing this global scourge.

UNDP’s global project “Ending Gender-Based Violence and Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals” seeks innovative ways to address gender-based violence (GBV), including through integrating GBV programming within large-scale sectoral development programmes and applying participatory ‘planning and paying’ approaches. Pilots in Iraq and Lebanon adapted an evidence-based model called “Indashyikirwa” (Agents of Change) integrating with women’s economic empowerment projects. This report compares “Indashyikirwa” adaptation experiences, processes and outcomes in these two settings

The guide is designed to provide the staff of Women’s Bureaux (WBs) and their partners across the Caribbean with basic instructions regarding the design and implementation of Women’s Economic Empowerment Initiatives (WEEIs) as one means in particular of addressing the entrenched problem of violence against women and girls in the region. The Guide is intended to place its users in a stronger position to respond to the needs of the region’s women and the challenges posed by violence against women and girls (VAWG).

This report synthesises the findings of case studies of nine women’s economic empowerment projects implemented by UNDP in seven countries in the region: Djibouti, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Syria, Tunisia and Yemen, with a focus on fragile and conflict countries. It identifies lessons learned based on case studies and accordingly provides recommendations for women’s economic empowerment programming.

Livelihood and Economic Recovery Essentials E-course

This 2-hour self-paced course provides a brief overview of UNDP’s approach to Livelihood and Economic Recovery (LER) in crisis and fragile settings. The course is based on UNDP’s Guidance on Building Resilience Through Livelihoods and Economic Recovery (2022).

Digital Solutions for Livelihood and Economic Recovery Guide

Digital technologies provide opportunities to rebuild and strengthen livelihoods after crises and accelerate economic recovery. They can help people access market information and facilitate the exchange of goods and services when traditional market functions are disrupted by shocks. This guide offers key considerations and programmatic suggestions for implementing digital livelihoods and economic recovery with programming examples.

| ITC |

SheTrades.com is an online platform designed to support women’s participation in international trade by facilitating how women network, learn, and do business. SheTrades.com is a powerful free tool where individuals can join a global community of women entrepreneurs, business support organisations (BSOs), partners, and companies that are united in the goal of supporting women and communities along supply chains and promoting a fairer trade system for all.

SheTrades Outlook is an innovative policy tool that helps stakeholders assess, monitor and improve the institutional ecosystem for women’s participation in international trade, through quantitative and qualitative data.

| ILO |

Workplace Gender-based Violence and Harassment in Cambodia’s Construction Sector

Workplace Gender-based Violence and Harassment in Cambodia’s Construction Sector is a knowledge expert seminar exploring gender-based violence and harassment in construction: analysing experiences, responses, and lessons from a survey and interviews in cement factories and construction sites. Violence and harassment at work takes many forms but is often understood as an act or acts that cause physical or psychological harm or injury. Gender-based violence and harassment (GBVH) is a subset of workplace violence and harassment that involves processes of power and control designed to assert and reproduce gender roles.

An international forum for sharing results of the ILO’s Call for Papers on labour market transition of young women and men in developing countries. The Symposium offers an opportunity for researchers and development practitioners to discuss innovative research on themes of youth employment and labour market transitions and applicability to policy and programme advice and implementation.

Featured photo: UN Photo/Harandane Dicko. Persons featured in this photo are not necessarily CRSV survivors. This photo is used for illustrative purposes only.